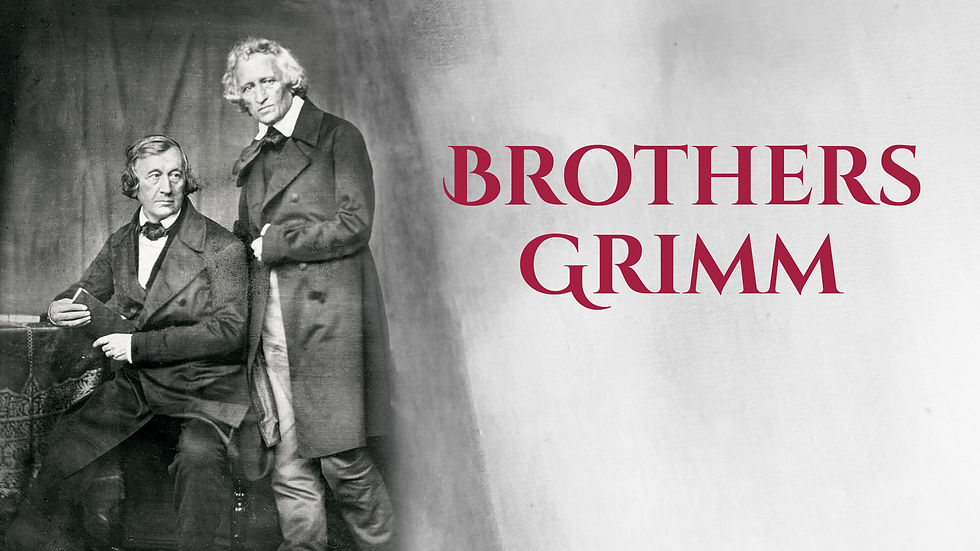

The Brothers Grimm

- gaymen2

- Sep 20

- 6 min read

The Brothers Grimm by Ann Schmiesing. The idyllic German childhood of the Grimm brothers, the great collectors and publishers of folklore, including "Cinderella," "Hansel and Gretel," and "Snow White", was ended by the premature death of their father:

“As for national and regional identity, the Grimms assumed as young boys that the rulers of Hessen-Kassel were superior to all others and that Hessen-Kassel was the most blessed of countries. Such assumptions likely went without saying, given their father's service to Hessen-Kassel as district magistrate, their grandfather Zimmer's career as councilman in the court of Kassel, and their maternal aunt Henriette Zimmer's position as lady-in-waiting to the landgravine in Kassel.

Yet the brothers also developed an appreciation for local custom more particularly while in Steinau. Having previously worn their shoulder-length hair loose, for example, they soon adopted the Steinau fashion of wearing it in a pigtail. Jacob was troubled by his mother's inability to bind his hair as firmly as local fashion dictated, however, and envied friends whose mothers succeeded in creating pigtails so firm that the hair took on a wooden appearance. The lifelong appreciation of rural environs and local traditions that Jacob and Wilhelm gained in Steinau accounts in part for their idealized depictions of folk culture in their writings.

“The overall happiness that characterized the Grimms' early years in Steinau also shaped such depictions. Later, the brothers would fondly recall their dignified father with his powdered pigtail and blue frock coat adorned with gold epaulettes and their mother so often engaged in knitting or sewing.

They remembered, too, the half-timbered magistrate's house with its walled courtyard and view of a neighbor's fruit trees, as well as their daily lessons and upbringing in the Reformed church. In the mornings, the siblings awoke to the sound of the teakettle. After the main meal, Philipp Wilhelm Grimm liked to inspect the livestock and garden. Young Jacob helped with grinding coffee, washing the porcelain, and collecting the eggs laid by the hens and ducks. The boys gathered acorn cups for their play, pretending that single cups were soldiers, two cups joined by a stem officers, and cups with gnarled or twisted stems drummers and trumpeters.

Every December, the children looked forward to the holiday plates of nuts and fruits customary in German homes and the gold and silver apples that hung from the lighted Christmas tree. In spring, they awaited the return of the storks that nested atop the town gate, coped with the occasional flooding of the Kinzig River, and searched for Easter eggs in a garden the family owned in a meadow north of town. In summertime, they collected insects, butterflies, and flowers and often later made sketches of them.

Their practice of collecting, analyzing, and saving specimens and mementos from their walks would continue throughout their lives and may have served as a foundation for their later collecting of texts and tales.

“While in many respects idyllic, the first few years of the Grimms' childhood in Steinau were not untouched by social and political tumult. The guillotining of Louis XVI in Paris so frightened the eight-year-old Jacob that he wrote of it to his grandfather Zimmer in Hanau, who sought to reassure Jacob that God often allows one ill in order to achieve more beneficial aims. For Jacob, Wilhelm, and their siblings, the upheavals of the time were not just far away in Paris, but on regular display in Steinau during the French Revolutionary Wars. French, Austrian, Dutch, Prussian, Mainz, and Hessian troops marched at various times through Steinau on the road that ran between Frankfurt and Leipzig.

A thousand Hessian soldiers marched through on one day alone in July 1792, with a total of six thousand more following at the end of the month. At times Saxon, Prussian, and Austrian units were quartered in Steinau, and on these occasions Steinau's inhabitants were required to provide food and lodging, albeit in exchange for some compensation. From November 1793 to the end of 1795, almost 479,000 troops passed through, accompanied by 235,000 horses.

“Steinau, with only some 1,400 inhabitants, was overwhelmed by this traffic. Rarely orderly, the troop marches led to frequent altercations between soldiers and townspeople, for which reason a fearful Dorothea Grimm kept her sons indoors whenever the regiments were present. Peering through a window, the Grimm siblings watched in fascination as cannons rolled by, each pulled by as many as ten draught horses.

They beheld soldiers peddling stolen silverware, porcelain, and books and darting into alleys to plunder additional wares. Soldiers on horseback rode off with bread and sausage speared with their sabers from roadside stands. Slaughtered chickens, geese, and goats hung from their kit bags, and some soldiers even punctured holes in bread loaves and then braided them into their horses' tails.

At every well and fountain, soldiers quenched their thirst. Drunken soldiers who could not keep pace with their regiments straggled alongside wagons carrying the seriously wounded and dying or heaped with slaughtered oxen, hogs, and calves. Shackled soldiers, many of them alleged spies, marched along with the regiments. Many soldiers were barefoot and disheveled and some had a bandaged head or an arm in a sling, but they nevertheless sang cheerfully to the music of violins. Pet squirrels, ravens, or magpies perched atop their kit bags. The soldiers took whatever wood they could find for their fires, including the railings enclosing the Grimms' flower beds.

Townspeople were at times forced to give hay and straw to the livestock herds that followed the regiments. On one occasion, the Grimms' maid smoked out the barn with juniper in an effort to safeguard the family's cows from a cattle plague that broke out among the regiments' herds and spread rapidly to the local livestock. Until the contagion subsided, the Grimms avoided their cows' milk and drank only water or tea.

“Despite the tumult of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Grimm family led a joyful life in Steinau until the early hours of January IO, 1796, when at the age of forty-four Philipp Wilhelm Grimm died of pneumonia. Jacob had turned eleven only days earlier, Wilhelm was just over a month away from his tenth birthday, and their four siblings ranged in age from eight to two. Philipp Wilhelm had grown seriously ill shortly before Christmas, and Jacob described in a letter of January 5, 1796, to his grandfather Zimmer the bloodletting and medicaments with which two doctors tried to cure him. His condition appeared to improve, such that Jacob asked his grandfather to send a courier with a loaf of freshly baked multigrain bread from a favorite Hanau bakery for his father's growing appetite. But Philipp Wilhelm's condition again worsened, and the requested loaf arrived too late. Ludwig recalled how Aunt Schlemmer grew increasingly distraught as she watched over the Grimm children in their father's final hours. On the morning of Philipp Wilhelm's death, Jacob awoke to voices in the neighboring room. He allegedly opened the door partway to find a carpenter taking measurements of his father's body and remarking that the well-respected magistrate deserved a coffin of silver, not wood. Only a few lines into an autobiographical essay published in 1831, Jacob related that he could still see in his mind his father's black coffin and the pallbearers with lemons and rosemary in their hands.

“The Grimms' memories, however idealized, of the life lived before the death of their father would later serve as refuge and inspiration at times of hardship. Wilhelm's nightly dreams as an adult often took him back to the magistrate's house and its emotional and material comforts.

Traveling in France in 1814 after the end of the French occupation of Hessen-Kassel but while battles continued to rage on French soil, Jacob sought to ease his homesickness by drafting an essay recounting his childhood and family. Yet the Grimms' later works also attest to the enduring psychological impact of their father's premature death, which ended their happy childhood. In an April 1818 letter to his mentor Savigny, Jacob, then thirty-three years old, attributed his inner unrest and extreme work habits to his assumption that he would die young like his father and thus needed to accomplish whatever he could before middle age.

Not even teenagers when their father died, Jacob and Wilhelm at once understood that the trajectories of their personal and professional lives had abruptly and incalculably changed.”

-----------------------------------------------

---------------------------------------------

copyright © 2025

All rights reserved.

TO BE DELETED FROM OUR SYSTEM

Return this e mail with

PLEASE DELETE OH HANDSOME ONE...

Our mailing address is

Hamilton Hall Hotel

1 Carysfort Road

Bournemouth

Dorset BH14EJ

01202-399227-

Comments